In recent years, cannabidiol (CBD) has gained popularity as an ingredient in cosmetic skincare products. CBD, a key compound derived from the cannabis plant, is distinct from THC in that it has no psychoactive effects. Several studies have highlighted CBD’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and moisturising properties, making it a promising addition to skincare formulations. Let’s delve deeper into how to meet compliance with CBD cosmetics regulations and a safe CBD use in cosmetic products.

CBD has been shown to help reduce sebum production in the sebaceous glands, which may aid in preventing acne. It can also alleviate inflammation and promote the healing of skin wounds. Additionally, its antioxidant properties protect the skin from free radical damage and premature ageing.

CBD is being studied for its potential in managing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, offering hope for those seeking effective skincare solutions.

Many cosmetic manufacturers have incorporated CBD into skincare products such as creams, serums, masks, and lip balms. However, it is crucial to select high-quality products and carefully review their ingredients to avoid potential allergens. Additionally, consumers must remain aware of the regulatory landscape governing CBD use in cosmetic products.

Particular attention should be given to the presence of impurities, especially psychotropic THC, to ensure product safety and compliance.

Key Considerations For CBD Use In Cosmetic Products

When using cannabidiol (CBD) in cosmetic products, it is essential to account for the potential presence of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a substance prohibited under Cosmetic Regulation 1223/2009. Specifically, THC is listed in Annex II of the Regulation, which prohibits “Narcotics: any substance listed in Schedules I and II of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs signed in New York on 30 March 1961.”

As THC may be present as a possible impurity in raw materials authorised for cosmetic use due to their composition, nature, or origin, it is necessary to establish a threshold limit. This threshold would determine the level at which THC, though prohibited, can be considered an acceptable impurity under Article 17 of the Regulation.

We continue by noting that cannabidiol (CBD) is currently under review for two safety-related aspects, one of which concerns the presence of traces or impurities of psychotropic substances in CBD. On 19 November 2020, the European Court of Justice (CJEU), in the Kanavape case (case C-663/18), ruled that CBD should not be considered a drug under the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

This applies even when CBD is extracted from the entire hemp plant, including leaves and flowers, as CBD itself, according to the CJEU, “it does not appear to have any psychoactive effects recognised in the current state of scientific knowledge.”

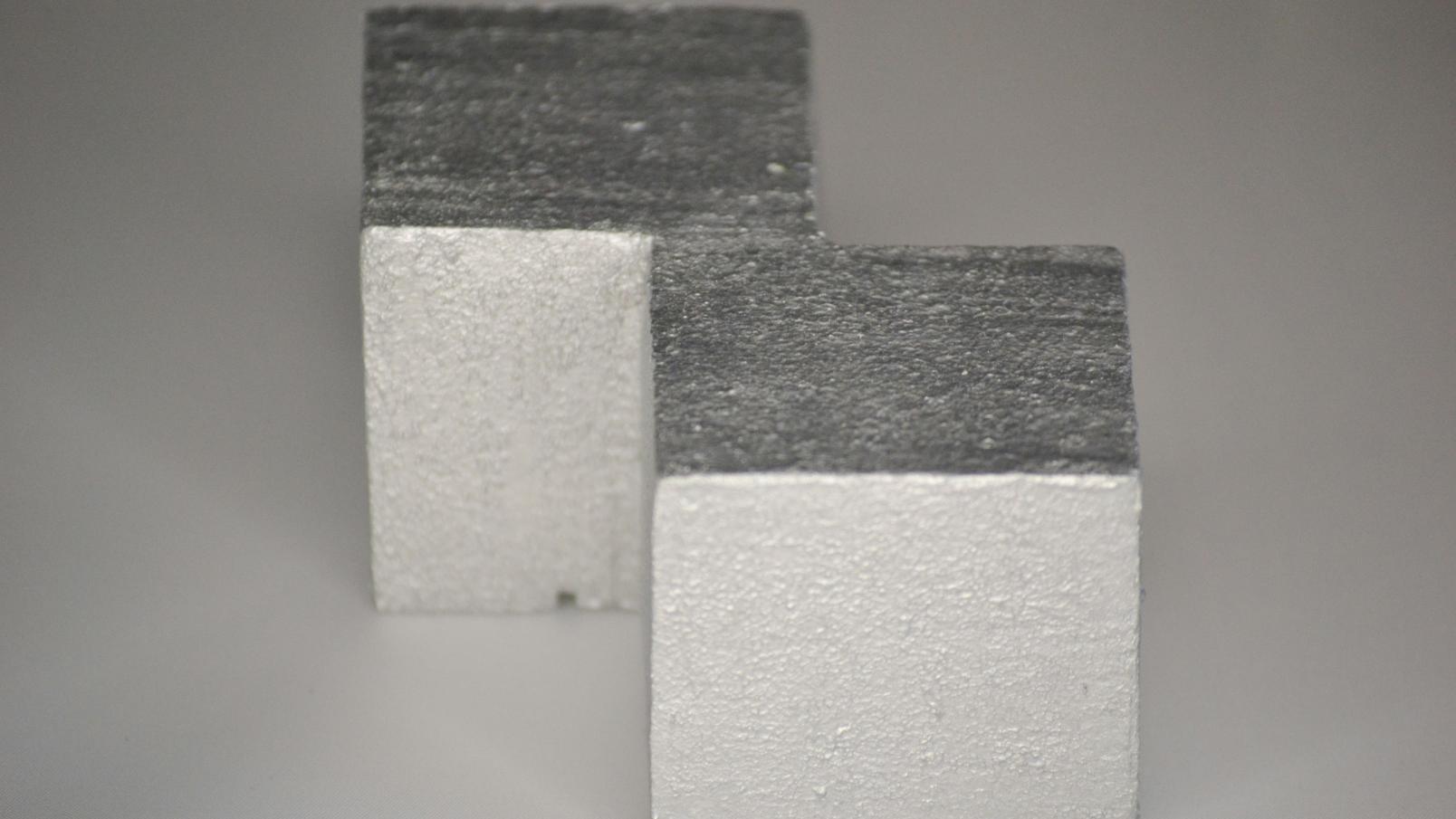

Following this ruling and the requests of the European Industrial Hemp Association (EIHA), prohibitions on Cannabis sativa L. (previously restricted under Annex II, item 306: narcotic) have been removed. Additionally, new INCI entries have been introduced to the (non-binding) CosIng database. This includes a specific entry for cannabidiol (CBD) listed as “CANNABIDIOL – derived from cannabis extract or tincture or resin.”

In practical terms, this ruling means that within the EU, not only leaf extracts but also natural CBD can be used in cosmetics, whereas previously only synthetic CBD was permitted. However, the judgment does not specify the required purity levels for CBD, the permissible THC content, or the acceptable levels of other relevant substances.

Concerns have been raised by Member States and civil society organisations about the CBD use in cosmetic products, particularly regarding the limited information available on its safety in such products and the potential risks to consumer health. As a result, the European Commission plans to request the SCCS (Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety) to conduct an assessment of CBD’s safety in cosmetics.

This assessment would include evaluating the levels of THC that could be deemed safe as traces or impurities in finished cosmetic products containing CBD or other hemp- and cannabis-derived ingredients.

Taobé is committed to closely monitoring legislative developments in this area and is aware of a “call for data” initiated by the European Commission, which remained open until October 2024. This initiative, along with the subsequent SCCS evaluation, aims to establish precise and comprehensive guidelines, as well as a regulatory update to address the currently undefined aspects.

In the meantime, Taobé advises its client companies to systematically carry out specific analyses on each batch to ensure that the presence of psychotropic substances, such as THC, does not exceed the acceptable limit.

Until the anticipated regulatory clarifications are provided, reference should be made to the existing legislative framework, even where it pertains to categories outside the scope of cosmetics.

Determining A Compliant Limit For Impurities

Therefore, in defining a precise limit for the presence of the aforementioned impurity in the finished product, and in the absence of a clear threshold or the pending evaluations of the SCCS (as mentioned above), it is important to take the following considerations into account:

- The WHO’s Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) has proposed an amendment to the 1961 Convention, suggesting that a note be introduced saying “all preparations containing predominantly cannabidiol and not more than 0.2% THC are not considered to be under international control”.

- One of the interesting conclusions of the aforementioned 2020 judgment of the CJEU can be found in paragraph 72, which reads: “However, it should be noted that, from the information in the file available to the Court and which is summarised in paragraph 34 of the present judgment, it is apparent that the CBD at issue in the main proceedings does not appear to have psychotropic effects or harmful effects on human health on the basis of the available scientific data (as already described). Moreover, according to those documents in the file, the variety of cannabis from which that substance was extracted, which was lawfully cultivated in the Czech Republic, has a THC content of no more than 0.2%.” From this point it could therefore be inferred that below a value of 0.2% THC, no psychotropic effects are detectable and, above all, that there are no harmful effects on health.

- At a European level there are different regulatory contexts, depending on the country of reference; on Italian soil (to give an example of context) the regulatory framework is defined by LAW 2 December 2016, no. 242 containing provisions for the promotion of the cultivation and agro-industrial chain of hemp. Article 1 specifically refers to “Support and promotion shall cover the cultivation of hemp with a view to: […] (d) the production of food, *COSMETICS*, biodegradable raw materials and innovative semi-finished products for industries in different sectors”;

This law also defines (Article 4, paragraph 5) a percentage limit of use beyond which the plant can be marketed. It reads: “If, as a result of the control, the total THC content of the crop is found to be higher than 0.2 percent and within the limit of 0.6 percent, no responsibility shall be placed on the farmer who has complied with the requirements of this law.”

Given that this limit is currently set at 0.3% (as per European Regulation 2021/2115, Article 4, paragraph 4, point c), it is worth noting that this provision does not theoretically apply to finished cosmetic products. However, Article 1 of the Regulation acknowledges the potential use of such derivatives in cosmetics. Therefore, this limit provides a useful reference for establishing a numerical threshold value.

In addition to this, Regulation 2021/2115 in Preamble 18, states:

“With regard to areas used for hemp production, in order to preserve public health and to ensure consistency with other legislation, the use of seeds of hemp varieties with a tetrahydrocannabinol content not exceeding 0,3 % should be included in the definition of eligible hectare.” where the emphasis is also on the concept of “public health”.

Returning to Law 242 of 2016, which refers to the THC limit for food consumption in Article 5, this is further linked to Regulation 1881/2006 (revised and replaced by Regulation 2023/915). This regulation defines the maximum impurity levels of THC in hemp seed oil (7.5 ppm / 0.00075%) and dry foods such as hulled hemp seeds, flour, and protein powder (3 ppm / 0.0003%).

However, these limits cannot be applied when defining an impurity threshold for a cosmetic product. This is because the CBD derivative in question (with potential traces of THC) is either an extract, not an oil, or a derivative not from seeds, and, most importantly, it is not intended for food consumption (the product is never ingested).

In addition to the points discussed so far, reference can be made to the judgement of the Italian Supreme Court (United Sections no. 30475/2019). The Court affirmed the principle that the transfer, sale, and general marketing of derivatives from Cannabis sativa L., such as leaves, inflorescences, oil, and resin, constitutes a criminal offence under Article 73 of Presidential Decree 309/90 (Consolidated Law on Italian Drugs), even when the delta-9-THC content is below the levels specified in Article 4, paragraphs 5 and 7 of Law 242/16.

However, the Court added an important clarification: “… unless such derivatives are, in practice, devoid of any doping or psychotropic efficacy, according to the principle of offensiveness”.

Let’s explore this point further. In relation to the active ingredient delta-9-THC, there is, as previously mentioned, no precise quantification in the literature or legislation linked to the concept of a “doping dose.” The only reference to the concept of a “narcotic threshold” is found in a note from the then Minister of the Interior, Hon. Matteo Salvini, from July 2018.

This was later incorporated into the operational guidelines communicated in the Directive on the marketing of hemp (no. 11013/110) of 9 May 2019, which states:

“inflorescences with a content of more than 0.5% fall under the notion of narcotic substances. For cannabis, both forensic toxicology and the scientific literature identify this threshold at around 5 mg of delta9-THC, which in percentage terms is equivalent to 0.5%, calculated on a 1-gram packaged joint/cigarette.” (excerpt also from Trattato di toxicologia Forense – Bertol, Lodi, Mari, Marozzi-ult. ed. 2000, available online).

According to this indication, and stepping away from the cosmetics topic to consider the matter more broadly, it would be possible to establish a minimum threshold below which the hemp product loses any intoxicating efficacy (narcotic and/or psychotropic).

For instance, to reach a doping dose of 25 mg of delta-9-THC, as outlined in the tables of Presidential Decree 309/90 (Consolidated Law on the regulation of narcotic and psychotropic substances), a hemp cigarette with a delta-9-THC content of 0.5% would need to weigh at least 5 grams (a large cigarette), rather than the 1 gram commonly associated with a conventional handcrafted cigarette.

This is akin to saying that to achieve a minimal psychotropic effect (intoxication) from a drink with an alcohol content of 2%, one would need to ingest 10 litres at once.

Based on this reasoning, it can be concluded that below a delta-9-THC content of 0.5%, the substance is devoid of psychoactive effects. Consequently, it is not suitable for recreational use but is more aligned with industrial or agri-food applications, as stipulated in Law 242/2016.

In addition to this, data demonstrating an interaction between CBD and THC can be considered when they are present in the same preparation, as in the case of the product under evaluation.

It has been known since the 1970s that high concentrations of CBD can attenuate the psychotropic effects of THC. Russo E., Guy G.W. (2006) in their publication A tale of two cannabinoids: the therapeutic rationale for combining tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol (Med. Hypotheses 66: 234-46), highlight that as CBD concentrations increase, the toxic effects of THC are significantly reduced in an in vitro model of cerebral ischemia.

To further support the relevance of this interaction, there is the proposal to use CBD as a therapeutic treatment to alleviate the symptoms of cannabis use disorder, which results from the abuse and misuse of THC. Details of this can be found in the article Cannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis use disorder.

Further confirmation of CBD’s antagonistic activity in relation to THC can be found in the study Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. This study demonstrates that, from a pharmacodynamic perspective, the simultaneous presence of high quantities of CBD can further reduce the activity of any residual THC.

It can therefore be concluded that the potential low THC content in the product, combined with CBD’s mitigating properties on the psychotropic effects of THC, ensures that the material would not exhibit narcotic effects if it remains below the threshold values outlined in these considerations.

Final Thoughts On CBD Cosmetics Compliance

There are no precise definitions at the cosmetic level regarding what value can be considered a trace or impurity (and therefore permissible as long as the cosmetic product is deemed safe). However, if a company adheres to cosmetic GMP, the unintentional presence of a small amount of a substance—arising from the inherent nature of raw materials, all allowed under the Cosmetics Regulation—may be considered compliant.

Article 17 of the Cosmetics Regulation states:

“The unintentional presence of a small quantity of a prohibited substance, resulting from impurities of natural or synthetic ingredients, the manufacturing process, storage, migration from the packaging and which is technically unavoidable despite the observance of good manufacturing practices, shall be permitted provided that such presence is in accordance with Article 3.”, (Article 3 ensures that a cosmetic product must be safe for use).

Ultimately, efforts have been made to define the concept of “small quantity.” Based on the most precise and relevant considerations available, Regulation 2021/2115, which further reduces the limit to 0.2%, could serve as a reference.

In the writer’s opinion, the limits of 3 ppm and 7.5 ppm (depending on the starting components) described by Regulation 2023/915, which establishes maximum values for certain food contaminants, would not be considered relevant as the product does not fall under the food category. This Regulation pertains to food products and is therefore not applicable to cosmetics, as the product in question will never be ingested.

For completeness, it is worth noting an additional document that may be considered: the EIHA position paper. In this document, the EIHA association proposed limits for the presence of THC impurities in cosmetics, which are lower than those identified so far.

However, this document is neither binding nor appears to have been considered by the European Commission. Moreover, it dates back to 2019, and the regulatory landscape for these products has evolved significantly since then.

The context remains highly nebulous, unfortunately. Clarity is expected from the SCCS committee, which, as noted, is anticipated to take a position after October 2024. It is important to emphasise that all limits and considerations presented in this article are based on rational analysis of the information currently available in the literature (both legal and otherwise).

Do you have questions about your CBD product? Keep in mind that, as of now, the regulatory framework may vary from country to country in the absence of a unified Community Regulation or Opinion. Contact us—we’ll be happy to assist you.